The following is the result of research I have been doing for an article on Religious Affections that I am writing for an Encyclopedia on Jonathan Edwards that will be published later this year by Eerdmans.

When I was 19 years old my father purchased a copy of Religious Affections for me and said, “I think you are ready for some meat.” He was not mistaken, it is a very meaty book that gets to the core of the purpose of God’s grace—to transform your heart so that your life is more and more marked by Christ’s own holy character. It is a book I have read and re-read many times over the years and is my favorite of his works and I highly recommend it to you. The article below is a summary of the book and I have posted it in the hope that it might whet your appetite for more of it.

All the quotes are from the 26 volume series of The Works of Jonathan Edwards published by Yale University Press (1957-2008). To make reading easier I have ended the quotes simply with the volume number and page number (i.e., 25:146 means volume 26, page 146).

***

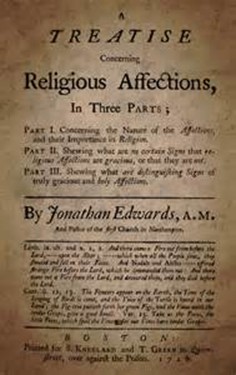

A Treatise on Religious Affections (1746) has proven to be one of Edwards’ most widely read and influential works, and has come to be viewed as a classic in Christian literature; its popularity and influence attested to by the fact that since its original publication it has never been out of print. In addition to multiple publications in America, various editions and abridgments have been published in England, Scotland, the Netherlands, and China, and has been translated into Dutch, Welch, and Chinese. Religious Affections represents the capstone of Edwards’ published thoughts on his experience in Connecticut River Revival (1734) and the Great Awakening (1740-42). Unlike Edwards’ previous works on revival that focused more on discerning whether or not a revival was a true work of God, Religious Affections asks a more personal and individual question: “What is the nature of true religion? and wherein do lie the distinguishing notes of that virtue and holiness, that is acceptable in the sight of God” (2:84).

The treatise is divided into three parts. Part 1 begins with an exposition of 1 Peter 1:8, from which Edwards concludes that the Scriptures clearly teach “that true religion, in great part, consists in the affections” (2:99). The human soul has two faculties, speculative understanding whereby the person can know things, and inclination whereby the person either approves or disapproves towards the things he knows. This faculty, Edwards explains “is sometimes called the inclination: and, as it has respect to the actions that are determined and governed by it, is called the will: and the mind, with regard to the exercises of this faculty, is often called the heart” (2:96).

Edwards notes three levels or “degrees” of intensity in the inclinations of the heart. The first, Edwards simply refers to as inclinations where “the soul is carried but a little beyond a state of perfect indifference” (2:96). The second are affections, which he defined as “the more vigorous and sensible exercises of the inclination and will of the soul” (2:96) such as love, hate, zeal, fear, hope, sorrow, and joy. The third degree of inclinations he calls passions. Passions differ from affections in that passions’ “effects on the animal spirits are more violent, and the mind more overpowered, and less in its own command.” So affections are strong inclinations of the heart that “(through the laws of the union which the Creator has fixed between soul and body) the motion of the blood and animal spirits begins to be sensibly altered; whence oftentimes arises some bodily sensation, especially about the heart and vitals” (2:96), yet which leaves the mind in command.

If there is anything that merits “vigorous exercise of the will, it is religion. “The things of religion are so great, that there can be no suitableness in the exercises of our hearts, to their nature and importance, unless they be lively and powerful. In nothing, is vigor in the actings of our inclinations so requisite, as in religion; and in nothing is lukewarmness so odious” (2:99-100). The affections, he asserts, are serve as the driving force behind a person’s actions, “they are the springs than set men agoing, in all the affairs of life, and engage them in all their pursuits” (2:101). Edwards goes so far as to say that “there never was any considerable change wrought in the mind of conversation of any one person, by anything of a religious nature, that he ever he read, heard or saw, that had not his affections moved” (2:102). Edwards then shows that a study of the Scriptures reveals that affections (such as listed above) play a very central and vital role in the Christian life, and serve as the signs whereby we can be assured God’s grace is actively at work in us; and conversely, the lack of which shows the absence of God’s saving grace.

Beginning with the assumption that he has proven his point that affections lie at the heart of the life of the true saint, in part 2, Edwards begins by stating that not all affections are truly “gracious” and therefore it is important to not just be satisfied that one has religious affections, but must know the difference between natural affections that any person can have and gracious affections caused by the work of the Holy Spirit. Edwards outlines twelve signs which neither prove nor disprove one’s affections to be truly gracious. It neither proves nor disproves saving grace if one’s affections,

- are raised to a high degree.

- have a great effect on the body.

- cause the person to talk much of religion.

- did not come about in one’s own contrivance or strength.

- bring Scripture texts to mind.

- have an appearance of love in them.

- are many and varied in kind.

- follow awakenings and convictions of conscience in a certain order.

- lead to being active in worship and the external duties of the Christian faith.

- dispose him or her to verbally praise and glorify God.

- give the person a spirit of confidence in their divine state with God.

- are pleasing to godly people and are looked upon by them as really gracious.

These signs are, in effect, false positives when it comes to discerning the sanctifying work of the Holy Spirit in one’s life. While Edwards agrees that these twelve signs were desirable and even expected and hoped for in the Christian’s life, nevertheless none of them are shown in Scripture as sure signs that a person is living in the power and influence of God’s sanctifying grace.

Part 3 offers twelve positive signs that Edwards argues Scripture lays out that one can look for to discern truly gracious affections from merely natural ones. Before beginning to share what these distinguishing sign are, Edwards makes some clear exhortations to the reader about the limits and proper use of these signs. First, knowing these signs will not “enable any certainly to distinguish true affection from false in others” (2:193). They are for personal examination only, not for judging the salvation of others. Second, knowing these signs will not aid in cultivating assurance in those truly saved Christians “who are very low in grace, or are such as have much departed from God, and are fallen into a dead, carnal and unchristian frame” (2:193). And third, Edwards asserts that these signs will not convict hypocrites “who have been deceived with great false discoveries and affections, and are once settled in a false confidence, and high conceit of their own supposed great experiences and privileges” (2:196). With these exhortations firmly in mind, Edwards proceeds to show what he believed were twelve reliable signs Scripture gives that distinguish true gracious affections from false. True gracious religious affections,

- are a result of the Holy Spirit living vitally in the person.

- come from first from a love for God Himself as opposed to a self-interest in His love towards us.

- love the moral excellence of holiness.

- are a result of correct knowledge about divine things, which are found in Scripture.

- come with a conviction and a certainty that Christianity is true.

- come with an “evangelical humiliation,” a sense of our own unworthiness and need for God’s grace.

- result in a radical change of nature in the person in regard to God and holiness.

- give the person the character and attitude of Christ Jesus, especially forgiveness, love, and mercy.

- give the person a tender spirit.

- are constant and consistent in their exercise creating a “beautiful symmetry and proportion.”

- leave the person with a desire to continue excel in sanctification rather than to be satisfied with past accomplishments.

- result in Christian practice.

A fifth of the entire treatise (78 pages in the Yale edition) is devoted to the twelfth and final sign, which Edwards saw as not only a “great and distinguishing sign of true and saving grace,” but also the “chief of all the signs of grace” and the “principal sign” for examining one’s “sincerity of godliness” (2:406-407). Edwards’ emphasis on the importance of practice was in line with the Puritan theology of his day which saw the Christian faith as “the doctrine of living to God…by Christ” (22:86). This “doctrine” consisted of two kinds of knowledge: speculative knowledge, which consisted in knowledge of the Old and New Testaments; and practical knowledge which was given by the Holy Spirit, and consisted in a sense of the beauty of and desire for God and divine things which ultimately resulted in Christian practice. Practice, Edwards asserts is the end goal and purpose of the affections is to “incline persons to practice holiness” (2:394).Religious Affections embodies Edwards’ most sustained treatment of practical knowledge, what it looks like, and how one can most accurately discern it in one’s own life.

Edwards is one of my favorite of the oldies. Thanks for sharing!!

LikeLike