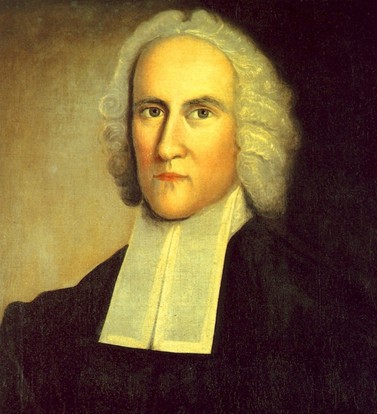

Tuesdays with Edwards!

Without a doubt, one of Edwards’ most important contributions was his book A Treatise Concerning

Religious Affections. When I was 19 years old my father purchased a copy for me and said, “I think you are ready for some meat.” He was not mistaken, it is a very meaty book that gets to the core of the purpose of God’s grace—to transform your heart so that your life is more and more marked by Christ’s own holy character. It is one of Edwards’ most widely read and influential works, and has come to be viewed as a classic in Christian literature; its popularity and influence attested to by the fact that since its original publication in 1746 it has never been out of print.

In Religious Affections Edwards asks a personal and individual question: “What is the nature of true religion? and wherein do lie the distinguishing notes of that virtue and holiness, that is acceptable in the sight of God” (page 84).

The treatise is divided into three parts. Part 1 begins with an exposition of 1 Peter 1:8, from which Edwards concludes that the Scriptures clearly teach “that true religion, in great part, consists in the affections” (page 99). The human soul has two faculties, speculative understanding whereby the person can know things, and inclination whereby the person either approves or disapproves towards the things he knows. This faculty, Edwards explains “is sometimes called the inclination: and, as it has respect to the actions that are determined and governed by it, is called the will: and the mind, with regard to the exercises of this faculty, is often called the heart” (page 96).

Edwards notes three levels or “degrees” of intensity in the inclinations of the heart. The first, Edwards simply refers to as inclinations where “the soul is carried but a little beyond a state of perfect indifference” (page 96). The second are affections, which he defined as “the more vigorous and sensible exercises of the inclination and will of the soul” (96) such as love, hate, zeal, fear, hope, sorrow, and joy. The third degree of inclinations he calls passions. Passions differ from affections in that passions’ “effects on the animal spirits are more violent, and the mind more overpowered, and less in its own command.” So affections are strong inclinations of the heart that “(through the laws of the union which the Creator has fixed between soul and body) the motion of the blood and animal spirits begins to be sensibly altered; whence oftentimes arises some bodily sensation, especially about the heart and vitals” (96), yet which leaves the mind in command.

If there is anything that merits “vigorous exercise of the will, it is religion. The things of religion are so great, that there can be no suitableness in the exercises of our hearts, to their nature and importance, unless they be lively and powerful. In nothing, is vigor in the actings of our inclinations so requisite, as in religion; and in nothing is lukewarmness so odious” (99-100). The affections, he asserts, are serve as the driving force behind a person’s actions, “they are the springs than set men agoing, in all the affairs of life, and engage them in all their pursuits” (101). Edwards goes so far as to say that “there never was any considerable change wrought in the mind of conversation of any one person, by anything of a religious nature, that he ever he read, heard or saw, that had not his affections moved” (102). Edwards then shows that a study of the Scriptures reveals that affections (such as listed above) play a very central and vital role in the Christian life, and serve as the signs whereby we can be assured God’s grace is actively at work in us; and conversely, the lack of which shows the absence of God’s saving grace.

Beginning with the assumption that he has proven his point that affections lie at the heart of the life of the true saint, in part 2, Edwards begins by stating that not all affections are truly “gracious” and therefore it is important to not just be satisfied that one has religious affections, but must know the difference between natural affections that any person can have and gracious affections caused by the work of the Holy Spirit. Edwards outlines twelve signs which neither prove nor disprove one’s affections to be truly gracious. These are essentially false positives, things that you expect a healthy Christian would be experiencing but are not things we should focus on to gain any assurance that the Holy Spirit is in fact at work in us.

Over the next few months we are going to look at these twelve things “which are no signs that affections are gracious, or that they are not” (127).

In this selection, Edwards gives the reasons why we should expect affections to be highly raised in Christians. Next week, we will look at why highly raised affections should not be looked at as a sure sign of the Spirit’s work.

You can read Religious Affections in its entirety at www.edwards.yale.edu. This selection is from Religious Affections, ed. John E, Smith, The Works of Jonathan Edwards, vol. 2 (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1959) Pages 127-130.

***

First, I would take notice of some things, which are no signs that affections are gracious, or that they are not.

1. ‘Tis no sign one way or the other, that religious affections are very great, or raised very high.

Some are ready to condemn all high affections: if persons appear to have their religious affections raised to an extraordinary pitch, they are prejudiced against them, and determine that they are delusions, without further inquiry. But if it be as has been proved, that true religion lies very much in religious affections, then it follows, that if there be a great deal of true religion, there will be great religious affections; if true religion in the hearts of men, be raised to a great height, divine and holy affections will be raised to a great height.

Love is an affection; but will any Christian say, men ought not to love God and Jesus Christ in a high degree? And will any say, we ought not to have a very great hatred of sin, and a very deep sorrow for it? Or that we ought not to exercise a high degree of gratitude to God, for the mercies we receive of him, and the great things he has done for the salvation of fallen men? Or that we should not have very great and strong desires after God and holiness? Is there any who will profess, that his affections in religion are great enough; and will say, “I have no cause to be humbled, that I am no more affected with the things of religion than I am, I have no reason to be ashamed, that I have no greater exercises of love to God, and sorrow for sin, and gratitude for the mercies which I have received?” Who is there that will go and bless God, that he is affected enough with what he has read and heard, of the wonderful love of God to worms and rebels, in giving his only begotten Son to die for them, and of the dying love of Christ; and will pray that he mayn’t be affected with them in any higher degree, because high affections are improper, and very unlovely in Christians, being enthusiastical, and ruinous to true religion?

Our text plainly speaks of great and high affections, when it speaks of rejoicing “with joy unspeakable and full of glory”: here the most superlative expressions are used, which language will afford. And the Scriptures often require us to exercise very high affections: thus in the first and great commandment of the law, there is an accumulation of expressions, as though words were wanting to express the degree, in which we ought to love God; “Thou shalt love the Lord thy God, with all thy heart, with all thy soul, with all thy mind, and with all thy strength.” So the saints are called upon to exercise high degrees of joy: “Rejoice,” says Christ to his disciples, “and be exceedingly glad” (Matthew 5:12). So it is said, Psalms 68:3, “Let the righteous be glad; let them rejoice before God; yea, let them exceeding rejoice.” So in the same Book of Psalms, the saints are often called upon to “shout for joy”; and in Luke 6:23 “to leap for joy.” So they are abundantly called upon to exercise high degrees of gratitude for mercies, to praise God with all their hearts, with hearts lifted up in the ways of the Lord, and their souls magnifying the Lord, singing his praises, talking of his wondrous works, declaring his doings, etc.

And we find the most eminent saints in Scripture, often professing high affections. Thus the Psalmist speaks of his love, as if it were unspeakable; Psalms 119:97, “Oh how love I thy Law!” So he expresses a great degree of hatred of sin; Psalms 139:21–22, “Do I not hate them, O Lord, that hate thee? And am I not grieved with them that rise up against thee? I hate them with perfect hatred.” He also expresses a high degree of sorrow for sin: he speaks of his sins going over his head, as an heavy burden, that was too heavy for him; and of his roaring all the day, and his moisture’s being turned into the drought of summer, and his bones being as it were broken with sorrow. So he often expresses great degrees of spiritual desires, in a multitude of the strongest expressions which can be conceived of; such as his longing, his soul’s thirsting as a dry and thirsty land where no water is, his panting, his flesh and heart crying out, his soul’s breaking for the longing it hath, etc. He expresses the exercises of great and extreme grief for the sins of others, Psalms 119:136. “Rivers of water run down mine eyes, because they keep not thy law.” And v. 53: “Horror hath taken hold upon me, because of the wicked that forsake thy law.” He expresses high exercises of joy, Psalms 21:1. “The king shall joy in thy strength and in thy salvation how greatly shall he rejoice!” Psalms 71:23, “My lips shall greatly rejoice, when I sing unto thee.” Psalms 63:3–7, “Because thy loving-kindness is better than life, my lips shall praise thee. Thus will I bless thee, while I live: I will lift up my hands in thy name: my soul shall be satisfied as with marrow and fatness, and my mouth shall praise thee with joyful lips: when I remember thee upon my bed, and meditate on thee in the night watches; because thou hast been my help, therefore in the shadow of thy wings will I rejoice.”

The apostle Paul expresses high exercises of affection. Thus he expresses the exercises of pity and concern for others’ good, even to anguish of heart; a great, fervent and abundant love, and earnest and longing desires, and exceeding joy; and speaks of the exultation and triumphs of his soul, and his earnest expectation and hope, and his abundant tears, and the travails of his soul, in pity, grief, earnest desires, godly jealousy and fervent zeal, in many places that have been cited already, and which therefore I need not repeat. John the Baptist expressed great joy (John 3:39). Those blessed women that anointed the body of Jesus, are represented as in a very high exercise of religious affection, on occasion of Christ’s resurrection; Matthew 28:8, “And they departed from the sepulcher with fear and great joy.”

‘Tis often foretold of the church of God, in her future happy seasons here on earth, that they shall exceedingly rejoice; Psalms 89:15–16, “They shall walk, O Lord, in the light of thy countenance: in thy name shall they rejoice all the day, and in thy righteousness shall they be exalted.” Zechariah 9:9, “Rejoice greatly, O daughter of Zion, shout, O daughter of Jerusalem; behold thy King cometh,” etc. The same is represented in innumerable other places. And because high degrees of joy are the proper and genuine fruits of the gospel of Christ, therefore the angel calls this gospel, “good tidings of great joy, that should be to all people” [Luke 2:10].

The saints and angels in heaven, that have religion in its highest perfection, are exceedingly affected with what they behold and contemplate, of God’s perfections and works. They are all as a pure heavenly flame of fire, in their love, and in the greatness and strength of their joy and gratitude: their praises are represented, as the voice of many waters, and as the voice of a great thunder. Now the only reason why their affections are so much higher than the holy affections of saints on earth, is, they see the things they are affected by, more according to their truth, and have their affections more conformed to the nature of things. And therefore, if religious affections in men here below, are but of the same nature and kind with theirs, the higher they are, and the nearer they are to theirs in degree, the better; because therein they will be so much the more conformed to truth, as theirs are.

From these things it certainly appears, that religious affections being in a very high degree, is no evidence that they are not such as have the nature of true religion. Therefore they do greatly err, who condemn persons as enthusiasts, merely because their affections are very high.